An import collapse, caused by the massive decline in oil production, is the main cause of Venezuela’s economic implosion. The fall in oil production began when oil prices plummeted in early 2016 but intensified when the industry lost access to credit markets in 2017.

Over the past five years, Venezuela has experienced the most pronounced decline in living standards seen by any country in recorded Latin American history. Between 2013 and 2018, real per capita income has shrunk by almost 40 percent – a decline that parallels those seen in Iraq and Syria during those countries’ recent armed conflicts. The nation has suffered staggering increases in malnutrition and around two million persons have left the country.

To say that the policies of Chávez and Maduro are to blame for this collapse is both true and trivial. Chavismo has been in power for almost twenty years now, so it is obvious that pretty much anything that is happening in Venezuela now – expect perhaps for last month’s earthquake – is the direct or indirect consequence of what it has done while running the country. But this tells us nothing about the mechanisms through which the country has become poorer and the reasons why we have seen this dramatic worsening emerge only in recent years.

In this piece, I present a framework for thinking about the economy’s performance that assigns a central role to the collapse in the country’s oil sector. I argue that Venezuela’s economy has imploded because it can’t import, and it can’t import because its export revenue has collapsed. While at the onset of the crisis the export decline could be blamed on oil prices, more recently it has been driven by the fall in oil production.

I also present some hypotheses about the key drivers of the contraction in oil output. I note that there are two inflexion points in the oil production series: early 2016, when oil prices fell below $30, and late 2017, when the oil sector lost access to international finance. I argue that during 2017 lending to Venezuela became progressively “toxic”, in the sense that financial intermediaries dealing with the country had to be ready to pay high reputational and regulatory costs. The resulting loss of access to credit appears to have helped precipitated the collapse in oil output, driving the resulting economic contraction.

Import collapse and the cash crunch

Let’s begin by focusing on the most obvious proximate cause of Venezuela’s economic collapse: the huge reduction in imports that took place in recent years. Between 2012 and 2017, imports of goods and services fell by a staggering 80.9%. In a highly import-dependent economy like Venezuela’s an import collapse is bound to cause a growth collapse.

Venezuela’s high import dependence is to a great extent a result of its high comparative advantage in oil as well as the failure of attempts to diversify its economy. The country’s non-oil sector is essentially devoted to the production and sale of goods with a very high import content, through which the economy spends the resources earned through its oil exports. When there are less dollars, the whole economy shrinks in tandem.

The data strongly bears out this relationship. The raw correlation between economic growth and import growth in Venezuela is 0.83; the elasticity of GDP growth to import growth is 0.23 percent. In other words, a 4 percentage point drop in imports leads to a 1 percentage point drop in GDP. This relationship explains pretty well the collapse in GDP over the past five years: between 2012 and 2017, GDP shrunk by one-third, while imports shrank by four fifths.[1]

This much is straightforward: Venezuelan living standards have collapsed because the economy can pay for many less imports than it did in the past. But why is it that the country can no longer pay for imports? Here we don’t have to look very far. Imports collapsed because exports collapsed. Back in 2012, Venezuela was selling almost $100bn to the rest of the world. Last year it sold $32bn.

Just like a person or a family, an economy that suffers a large decline in what it sells to other economies will be able to buy much less from them. Put simply, Venezuela suffered a two-thirds decline in its annual paycheck. Any country that suffers such a massive decline in its income is bound to experience a collapse in living standards.

Here an important caveat is in order. When an economy’s exports fall, that economy’s imports won’t necessarily decline immediately if the economy can borrow or dip into its savings in order to cushion the blow. That is why countries subject to high terms of trade volatility are well advised to save during boom times. And that is precisely what Venezuela didn’t do.

On this, the blame falls squarely to the government of Hugo Chávez, who led the economy during the largest external boom in its history and basically spent all of it. As a result of Chávez’s willingness to pour money into everything – from paying off nationalizations to buying the support of Caribbean countries with cheap oil – Venezuela ended up in a much more vulnerable position than just about any other oil exporting country when the shock hit. At the end of 2013, despite a prolonged period of buoyant oil markets that had taken the price of a Venezuelan barrel above $100, Venezuela’s international reserve were only $22bn, enough to pay for just 5 months of imports. By contrast, Saudi Arabia at the time had accumulated $725bn in reserves covering 5 years of imports.

However, borrowing or using your assets will only take you so far when your income falls permanently. Even if Venezuela had saved much more during the boom, it would have inevitably had to adjust its spending levels in response if export revenues failed to recover. A rainy-day fund could have helped it smooth out the adjustment over time, but an adjustment would have been inevitable sooner or later.

Venezuela’s disappearing export revenues

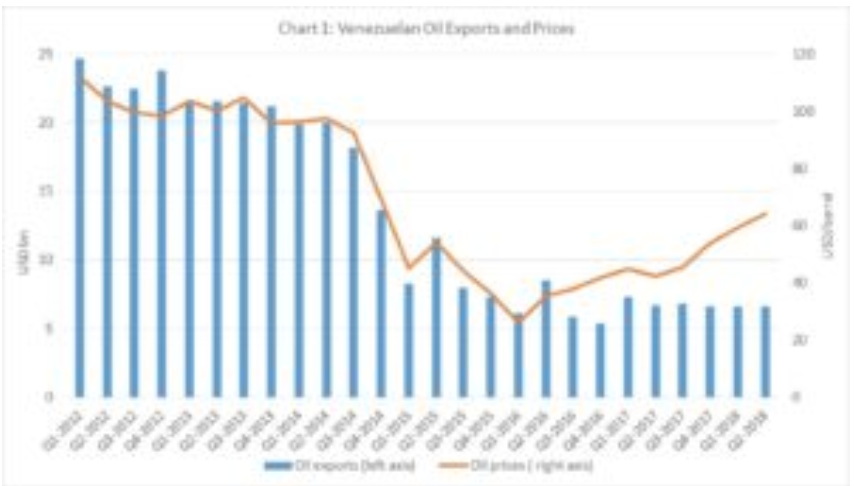

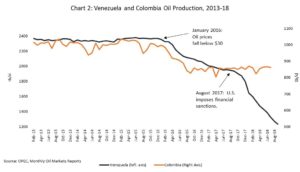

So what, then, is the explanation for the export collapse? Chart 1 above shows that exports track oil prices relatively well up until the first half of 2016. This means that the country was exporting a relatively constant number of barrels and that the decline in sales was caused by the fall in prices. However, from the second half of 2016 onwards, oil prices began to recover, but oil exports didn’t. The reason is that Venezuelan oil production had begun to fall, so that the country was selling less and less oil to the rest of the world. Chart 2 shows this phenomenon more directly, tracing how Venezuelan oil production plummeted by almost half between 2016 and 2018.

To understand the magnitude of this effect, consider how much Venezuela would be earning in oil export revenue today if production had not declined. Were the country selling as many barrels to the rest of the world today as in 2015, it would have exported $51bn in oil this year. By contrast, Venezuela will sell only $23bn of oil internationally in 2018 (and, if the slide in production continues, $16bn in 2019). We can safely say that if the country was receiving $28bn more in yearly export revenue than it does today, it would have experienced a much smaller decline in living standards than it saw.

The implosion of the oil sector

The bottom line is that if you want to understand Venezuela’s economic implosion, you have to understand what happened to its oil exports. There were of course a lot of misguided policies carried out by Chávez and Maduro in the past 20 years, but many of them – like, say, expropriations of large agricultural holdings – are largely irrelevant to oil production. Our analysis suggests that what we really have to focus on is what led to the decline of the oil sector.[2]

What seems most striking about the fall in Venezuela’s oil production is that it is a very discontinuous process. Oil production fell in the first few years of the Chávez administration but had largely stabilized after 2008. The decline that began in early 2016 comes after an 8-year period of stability in which in fact production had risen moderately. Chavismo during its first 16 years in power managed not to kill its golden cow, only to slaughter it in the last three years.[3]

The turning point came in early 2016. Between January of 2016 and August of 2017, the country lost 389tbd of production, or a monthly average of 19tbd. Then, in late 2017, the country’s oil sector goes into free-fall. Between August of 2017 and August of 2018, the country loses 701 tbd, for an average monthly decline of 58tbd, more than triple the absolute rate of decline of the prior 20 months. The data thus clearly shows two breaking points in the trend: the beginning of the initial decline, around January of 2016, and the acceleration of the decline, after August of 2017.

Usual and unusual suspects

Now, any analysis of causes using a country’s single time-series is speculative at best. Modern quantitative methods can’t offer decisive answers to questions about causality in non-experimental data even with very large data sets. Therefore, what one can say about the causes of the evolution of a single economy’s time trend is very limited. That said, it is still worthwhile to think through different hypotheses and ask whether they would lead to the patterns observed in the data.

The fact that the first stage of the decline starts in January 2016 points to the plunge in oil prices that happened at that moment. While oil prices had fallen steadily since mid-2014, they reached their lowest levels in years at the start of 2016. Venezuela’s oil basket hit a 13-year low of $21.6/bl towards the end of January, mirroring the collapse in global oil prices.

A production decline is what one would normally expect in any industry that sees a price plunge of this magnitude, particularly if it has a high marginal cost of production, as is the case for some of Venezuela’s eastern oil fields. In fact, private sector estimates show that up to 2016 the decline in production in the country’s traditional fields was being offset by production in the Orinoco Oil Basin joint ventures. In 2016, production in these heavier crude fields began to decline, pushing the trend in the overall series downwards.

For the purposes of comparison, Chart 2 plots the evolution of Colombian oil production during the same period. Venezuela’s neighbor also produces high-cost oil; after the bottom fell out from under oil prices, some of those barrels were no longer profitable to produce. As the figure shows, the decline in Colombia’s oil production during this period of time was quite similar in magnitude to that of Venezuela. This suggests that the initial stage of the production decline was in line with what can be explained based on the fall in profitability caused by the price collapse in a high-cost producer.[4]

What cannot be explained easily by the price decline is the collapse in production that takes place after August 2017, as prices were clearly on the upswing then. It is possible that this collapse can be explained as the cumulative effect of past underinvestment, which appears to have become worse as a result of the post-2016 cash crunch. In fact, official PDVSA data show that investment plunged by more than 50% between 2014 and 2016 (although this partly results from the accounting effects of currency depreciation, which lowered domestic costs of production).

However, the magnitude of the post-August drop in production caught many observes by surprise. Writing in April of 2017 IPD Latin America – perhaps the most prominent oil consultancy covering Venezuela – predicted in its “worst case” scenario a decline of 13% in production in 2017 and an annual average rate of decline of 6% in the subsequent three years. By contrast, production fell by 19% in 2017 and by 25% in the first eight months of 2018. Active rigs, often used as a leading indicator of production, had fallen in 2016 but stabilized in the first half of 2017, leading observers to expect that a stabilization of oil output would follow.

Sanctions and the toxification of Venezuelan debt

It is striking that the second change in trend in Venezuela’s production numbers occurs at the time at which the United States decided to impose financial sanctions on Venezuela. Executive Order 13.808, issued on August 25 of 2017, barred U.S. persons from providing new financing to the Venezuelan government or PDVSA. Although the order carved out allowances for commercial credit of less than 90 days, it stopped the country from issuing new debt or selling previously issued debt currently in its possession.

The Executive Order is part of a broader process of what one could term the “toxification” of financial dealings with Venezuela. During 2017, it became increasingly clear that institutions who decided to enter into financial arrangements with Venezuela would have to be willing to pay high reputational and regulatory costs. This was partly the result of a strategic decision by the Venezuelan opposition, in itself a response to the growing authoritarianism of the Maduro government.

The toxification of Venezuelan financing was much more of a discontinuous than a gradual process. As late as October 2016, Credit Suisse had structured a bond exchange without raising many eyebrows. At the time, the opposition-controlled National Assembly passed a resolution which criticized the economics of the arrangement but did not question its legality.

Six months later, the President of the National Assembly was writing letters to international banks warning them that if they lent money to Venezuela they would be not only violating Venezuelan law but favoring a government that was recognized as dictatorial by the international community.[5] When Goldman Sachs Asset Management purchased $2.8bn of bonds in May from the Venezuelan government through an intermediary, angry Venezuelans gathered to protest outside its New York office and the opposition vowed not to pay the bonds if it reached power. By the time that sanctions were approved in August, Venezuela had all but lost access to international financial markets as a result of the combination of continued poor policies and the toxification of its finance.

Our aim is not to assign responsibility to the opposition or the government for this political standoff. A reasonable case can be made that Venezuela’s opposition was completely within its prerogative to request that debt issuances be authorized by the National Assembly as well as to question the morality of lending to the Maduro government. Our point is that the spilling over of this political crisis into the arena of finance had consequences for the country’s economy and for the living standards of Venezuelans.

Sanctions had the effect of definitively closing the door on any possibility of a Venezuelan debt restructuring. Since the sanctions impeded the nation from accessing new financing, they also impeded it from issuing new bonds in exchange of old ones, the modality they would have needed to use to restructure bond debt. In fact, Maduro announced in November 2017 that he was creating a commission to restructure Venezuela’s debt, but that commission to this date has produced no results, largely because there seems to be no legal way in which U.S. investors can negotiate with it.[6]

Perhaps even more important than Trump’s Executive Order was a letter of guidance issued by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen) on September 20, 2017, warning financial institutions that “all Venezuelan government agencies and bodies, including SOEs [state-owned enterprises] appear vulnerable to public corruption and money laundering” and recommending that several transactions originating from Venezuela be flagged as potentially criminal.

Many financial institutions proceeded to close Venezuelan accounts, reasoning that the compliance risk of inadvertently participating in money laundering was not worth the benefit. Venezuelan payments to creditors got stuck in the payment chain, with financial institutions refusing to process wires coming from Venezuelan public sector institutions. Even CITGO, a Venezuelan-owned firm incorporated in Delaware, had trouble getting banks to issue it letters of credit.

These restrictions impacted Venezuela’s oil industry in several ways. First and most evidently, loss of access to credit stops you from obtaining financial resources that could have been devoted to investment or maintenance. As is often the case with event-study analysis, it is difficult here to build the counterfactual, as one can argue that Venezuela’s unsustainable policies would have led it to lose market access in 2017 even if its finance hadn’t become toxic. However, countries that lose market access typically have the possibility of regaining it after entering a debt restructuring process, a door that was closed to Venezuela after the Executive Order.[7]

There are also more direct links between finance and real activity that can lead a firm that gets closed off from financial ties to experience a decline in its productive capacity. For example, one of the most effective mechanisms that PDVSA had found to raise production in recent years was the signing of financing agreements in which foreign partners would lend to finance investment in a joint venture (JV) agreement as long as they could pay the loan from the JV’s production. The Executive Order effectively put an end to these loans.

Likewise, before sanctions were imposed, PDVSA had begun to refinance a significant part of its arrears with service providers through the issuance of New York law promissory notes. The Executive Order also put an end to these arrangements. What was unusual about PDVSA in 2017 was not that it had a large level of arrears – many oil producers had accumulated arrears after the price plunge. What was unusual is that it was unable to refinance them.

One reason why the loss of access to finance may have had a stronger effect on the Venezuelan economy than in other countries where similar sanctions have been imposed is that Venezuela is a highly indebted economy. For example, at the moment at which U.N. sanctions were imposed in 2006 on Iran, the country’s debt was only 9% of GDP – in contrast to Venezuela’s 110% ratio. Because of its high level of leverage, Venezuela’s oil sector was much more sensitive to changes in its access to financing than that of other, less levered oil exporters.

As we warned previously, these observations should not be taken as decisive proof that sanctions caused the output collapse. There are many other factors at play in the Venezuelan economy which can also be put forward as explanations. Maduro’s decision to appoint a general with no previous industry experience and the broad-ranging corruption investigation that led to the jailing of 95 industry executives, including two former PDVSA presidents, appear to have caused a paralysis in many of the sector’s professional cadres. The loss of the industry’s specialized human capital, part of the brain drain that accompanies large scale migration exoduses, also contributed to the deterioration of its operational capacity.

The data, however, strongly suggests the need for much more in-depth research on the reasons for Venezuela’s oil output collapse and for the discontinuous behavior in the series. The fact that the acceleration of the decline coincides with the onset of the country’s toxification to international investors suggests that we need to closely explore this channel as a potential driver of Venezuela’s output collapse.

Closer and more systematic analysis of the data can help us check the consistency of alternative competing hypotheses about the decline. For example, consider the effect of asset seizures by creditors in the decline of production. The only creditor that to date was able to directly impact PDVSA’s operational capacity was ConocoPhillips, when it received court orders in May of 2018 allowing it to seize products and assets in the Caribbean. While these seizures may have contributed to the production decline at the time, the fact that they took place almost ten months after the acceleration of the drop in oil production suggests that they are not a primary causal factor. (The standoff was resolved last month, yet there is no evidence that production has recovered since).

None of the foregoing is intended to exculpate the Maduro administration for its atrocious mismanagement of the economy during the past six years. In my view, it is a settled case that Venezuelans are much worse off today than they would have been under saner economic policies. The government’s decisions not to correct the huge real exchange rate and other relative price misalignments, to maintain expensive fuel subsidies while monetizing a double-digit budget deficit, and to persecute the private sector for responding to relative price signals all contributed to making Venezuelans’ lives miserable under Maduro.

But claiming that Maduro’s economic policies have caused a deterioration of living standards in Venezuela is not at odds with accepting the possibility that economic sanctions may have made things even worse. Most phenomena in social sciences have multiple causes. There is no logical reason why Maduro’s incompetence and misguided sanctions cannot both have contributed to the collapse in Venezuelans’ living standards.

Advocates of sanctions on Venezuela claim that these target the Maduro regime but do not affect the Venezuelan people. If the sanctions regime can be linked to the deterioration of the country’s export capacity and to its consequent import and growth collapse, then this claim is clearly wrong. While the evidence presented in this piece should not be taken as decisive proof of such a link, it is suggestive enough to indicate the need for extreme caution in the design of international policy initiatives that may further worsen the lot of Venezuelans.

The author is Chief Economist at Torino Economics, an economics consultancy firm in New York. I am grateful to María Eugenia Boza, Dorothy Kronick, Francisco Monaldi, Victor Sierra, David Smilde and William Neuman for their comments and suggestions, though I am totally responsible for any shortcomings of this piece.

[1] Elasticities are commonly estimated using natural logarithms to ensure that the estimate is invariant to the scale of the variables. A one-third reduction is equivalent to a 41 log-point reduction, while an 80 percent reduction is equal to a 166 log-point reduction. The ratio between these two declines, 25 percent, is very close to our elasticity estimate obtained using data from 1998 to 2015 (the last year in which the Central Bank published data). Logarithmic variations tend to be close approximations of percentage changes for small changes but can differ significantly, as is the case here, for large changes.

[2] See Monaldi, Francisco “La implosión de la industria petrolera venezolana” for a comprehensive discussion of the woes faced by Venezuela’s oil production. Monaldi discusses a number of coincident factors, including sanctions, lower prices, underinvestment and accumulation of arrears. Our piece attempts to move forward in the discussion of potential causes by looking at how the timing of these factors relates to changes in the time series of oil production.

[3] There are a number of different data series for Venezuelan oil production, and they differ with respect to the timing of the start of the decline. In Chart 2, we use OPEC’s data from independent secondary sources, which presents a stable trend until 2016. This is the series that OPEC uses, for example, to set production quotas. Data reported by the government to OPEC, as well as data from IPD Latin America, time the start of the decline earlier. Nevertheless, both of them show an acceleration of the decline at the start of 2016. They are thus consistent with our thesis that factors leading to a decline of oil output made themselves felt at the start of 2016.

[4] The series published by the Venezuelan government times the decline earlier, beginning in mid-2014. This would coincide with the start of the price decline rather than the low point of the price series.

[5] See, for example, the April 18, 2017 letter by National Assembly President Julio Borges to the CEO of Deutsche Bank.

[6] Although there is no legal impediment for institutions in other countries to participate in such a restructuring, non-U.S. creditor groups have shied away from any action that would impose restrictions on their capacity to do business in the U.S. and that would leave them with bonds that would not be tradable in U.S. markets.

[7] An argument can be made that Venezuela would not have been able to restructure even absent sanctions. In that argument, sanctions were not binding because they did not cause the closure of international financial markets. Given that the stated aim of the sanctions was precisely to restrict access to credit, this argument would also imply that sanctions were redundant and irrelevant. It is unclear what would be the rationale for maintaining sanctions in this line of reasoning, which is premised on the claim that they did not have their intended effect. In any case, the example of refinancing of commercial debts via issuance of promissory notes cited below shows that Venezuela was in fact restructuring some of its existing debts prior to the adoption of sanctions.