While corruption and organized crime are thriving amid Venezuela’s political and economic crisis, previously unpublished U.S. government drug trade monitoring data suggests that Venezuela is not a primary transit country for U.S.-bound cocaine. In “Beyond the Narcostate Narrative,” the authors assess the implications of official U.S. drug control data for prospects at advancing a peaceful, negotiated return to democracy in Venezuela.

When U.S. policymakers talk about Venezuela’s crisis, the flow of cocaine through the country is a frequent talking point. And there is no question that organized crime and corruption have flourished in the midst of Venezuela’s crisis. Yet the true extent of drug trafficking is often magnified by actors who suggest that a negotiated, democratic solution in Venezuela is impossible. The authors have heard some version of ‘you can’t negotiate with a narcostate’ countless times in recent years.

This paper uses the U.S. government’s own best estimates of transnational illegal cocaine shipments to gauge the scale and relative importance of Venezuela’s role as a transit country. In particular, we draw on recent data from the U.S. interagency Consolidated Counterdrug Database (CCDB), a multi-source collection of global illegal drug trafficking events that is gathered from intelligence data such as detection and surveillance, as well as interdiction and law enforcement data. According to the Department of Defense, “The CCDB event-based estimates are the best available authoritative source for estimating known illicit drug flow through the Transit Zone. All the event data contained in the CCDB is deemed to be high confidence (accurate, complete and unbiased in presentation and substance as possible).” We have supplemented CCDB estimates with public statements and presentations made by officials at the Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Defense, and Department of State regarding drug trafficking trends in the Americas.

Our main findings include:

- Venezuela’s state institutions have deteriorated and the country lacks an impartial, transparent, or even functional justice system. In this environment, armed groups and organized criminal structures, including drug trafficking groups, have thrived. But U.S government data suggests that, despite these challenges, Venezuela is not a primary transit country for U.S.-bound cocaine. U.S. policy toward Venezuela should be predicated on a realistic understanding of the transnational drug trade.

- Recent data from the U.S. interagency Consolidated Counterdrug Database (CCDB) indicates that 210 metric tons of cocaine passed through Venezuela in 2018. By comparison, the State Department reports that almost seven times as much cocaine (1,400 metric tons) passed through Guatemala the same year.

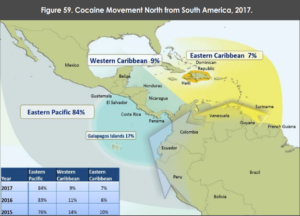

- According to U.S. monitoring data, the amount of cocaine trafficked from Colombia through Venezuela is significant, but it is a fraction of the cocaine that makes its way through other transit countries. Around 90 percent of all U.S.-bound cocaine is trafficked through Western Caribbean and Eastern Pacific routes, not through Venezuela’s Eastern Caribbean seas.

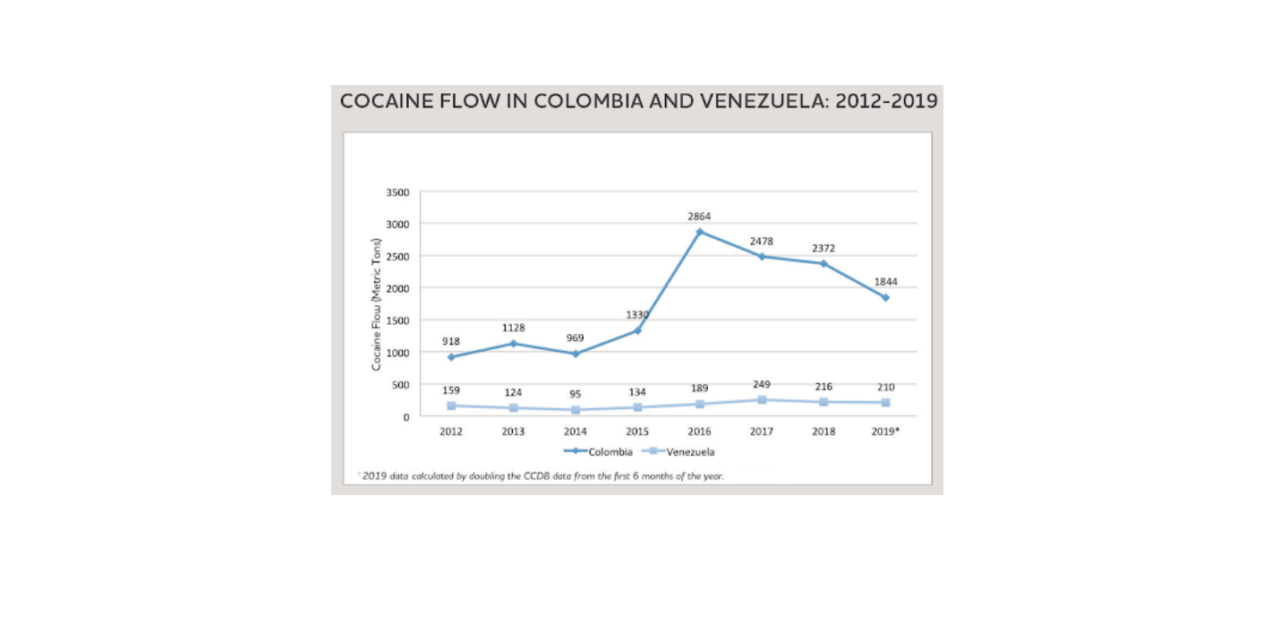

- There was an increase in cocaine flows through Venezuela in the period from 2012 to 2017, but that increase corresponds with a surge in cocaine production in Colombia during that same time. CCDB data suggests the amount of cocaine trafficked through Colombia rose from 918 metric tons in 2012 to 2,478 metric tons in 2017 (a 269 percent increase), and from 159 to 249 metric tons in Venezuela in that same period (a 156 percent increase). When cocaine trafficking in Colombia dropped slightly post-2017, cocaine flows in Venezuela fell as well.

- U.S. CCDB data shows that cocaine flows through Venezuela have fallen since peaking in 2017. According to CCDB data, the amount of cocaine flowing through Venezuela fell 13 percent from 2017 to 2018, and appeared to continue to fall slightly through mid-2019.

- A peaceful, negotiated, and orderly transition offers the best chance of allowing the reforms needed to address organized crime, drug trafficking, and corruption in Venezuela. The 2009 military coup d’etat and resulting turmoil in Honduras provides a cautionary tale for U.S. policymakers who see intervention or collapse as the best route for a return to democracy in Venezuela.

(Source: 2018 DEA Threat Assessment)

Drug trafficking is just one of the illicit economies running through the Venezuelan state. We focus on the illicit drug market here because of the availability of relatively good data. Sober analysis must be carried out on corruption in state food distribution and government contracts, as well as the growing trade in illicit gold and other minerals, in order to properly assess the size and importance of these illicit economies. Whatever the case, their existence only underlines the necessity of avoiding a disorderly, conflicted change in power.

With this in mind, we make four key recommendations for U.S. policymakers in this report:

- U.S. officials should devise and communicate a more flexible sanctions regime that incentivizes a negotiated electoral solution in Venezuela, which remains the most viable way to build state capacity against organized crime and corruption in the country. The U.S. government can and should offer Nicolas Maduro relief from financial and oil sanctions in parallel with agreements to conduct internationally-observed credible presidential elections, rather than insisting on Maduro’s resignation as a precondition—a demand which stymied negotiations in 2019.

- U.S. officials and Members of Congress should refrain from threatening a “military option” or pushing for an eventual collapse of the Maduro government under ever-harsher economic sanctions. Both strategies would impose profound hardships on the Venezuelan people, and would be detrimental to Venezuela’s neighbors as well as to U.S. interests. The presence of Colombian guerrilla groups and other pro-Maduro armed actors in Venezuela suggest that a “collapse” scenario would be chaotic and unpredictable, and any foreign military occupation would meet prolonged, violent resistance. It is very likely that both scenarios would see the continued growth of ungoverned spaces and illicit activity in Venezuela’s interior.

- The U.S. government does not have to wait until after a transition to address corruption in Venezuela. U.S. officials and Members of Congress should encourage a culture of transparency and accountability from Venezuela’s National Assembly. While United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funds are not directly managed by the National Assembly, USAID does support compensation, travel costs, and other expenses to its members. Given credible allegations of corruption against some National Assembly members, USAID should ensure that National Assembly President Juan Guaidó and his team insist on full transparency in the allocation of these funds.

- U.S. officials and Members of Congress should encourage Colombian authorities to implement a sustainable approach to containing and reducing coca cultivation and cocaine production by emphasizing rural development. By fully implementing the historic 2016 peace accords, the Colombian government could commit to the best long-term strategy for coca crop reduction: building a functioning civilian state presence in areas worst affected by the country’s armed conflict.