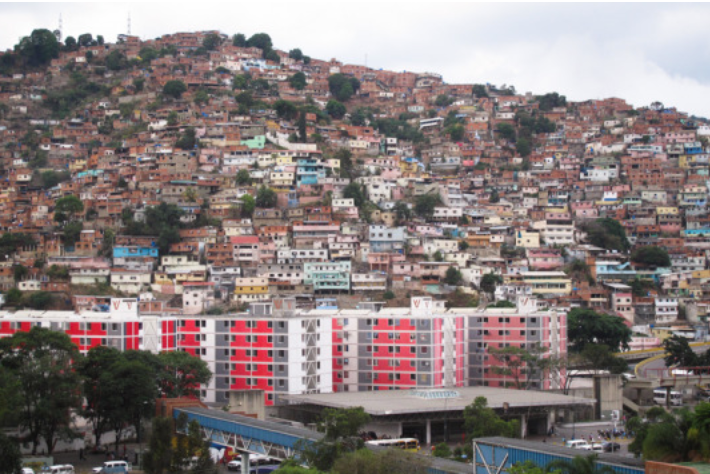

Caracas barrio of Antímano (photo taken from Caracasshots.blogspot.com)

[Yesman Utrera is Venezuela´s leading fixer and translator, facilitating the visits of many international journalists. He is also an accomplished journalist in his own right. When we cross paths three or four times a year I always ask him for an update on the barrio of Antímano (Southwest Caracas) where he lives. His comments are always nuanced and thoughtful. A while back I asked him to write an ethnography of conditions in his barrio and he sent me the following.]

About a month ago I went to a pharmacy to buy some baby-food for my daughter. It was 5 in the afternoon. People were lining up in a more or less ordered queue in the center of Antímano. People waiting in line told me they did not expect to be able to buy anything that same day, but they hoped to be the first ones in line for the next day.

Suddenly, someone tried to cut the line up towards the front. People started to complain; they began to shove and scream. The police tried to intervene and calm the situation, firing a couple of shots in the air. Rumors flew that the person cutting in line had payed off the police.

The people in line were not willing to tolerate this abuse. Insults and threats were becoming louder. Sensing the situation was slipping out of control, the police threatened to fire at the crowd. But the people kept on getting angrier. Police called reinforcements and started firing rubber bullets into the crowd.

Instead of panicking and desperately running for cover, the crowd calmly dispersed, sarcastically joking about the situation. Half an hour later they were back in line. The person who was cutting the line? He was now first in the queue.

Events like these are such common occurrences in today’s Venezuela that they no longer surprise anyone, least of all those who live in the less affluent barrios of Caracas. Scarcity has homogenized everyone into a single mass trying to find whatever they can to feed their families. “No one is middle class here; we’re all poor,” you hear in the streets.

The surest way to get food in the barrios is still by waiting in line. The Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAP) have been well received in Antímano, when they can deliver. But they are inefficient and intermittent.

Leonardo Guerrero (28) lives with his wife and three daughters in the area of Punta Brava of Antímano. He works as a motorcycle-taxi driver and waits for costumers in front of the local church. For him and his family the situation has become increasingly difficult since Chávez’s death.

We always backed Chávez because he ran the country well. You could buy anything and things were not expensive. I was able to build my own house by working with my motorcycle and I could provide for my girls in a normal way. But since Maduro is president it has been rough for me. Now I practically only work for food…When the (CLAP) bags arrive, I cheer because it is something good, but how long do they last? Not even a week. The food flies.

To buy food from the re-sellers, or bachaqueros, is almost impossible for Leonardo’s family, so he has to line up to buy price-controlled goods two times a week, the days assigned to his ID number. He has also changed his diet: “now we only eat potatoes, cassava, and plantain. We make lots of soups.”

The CLAPs were created by the government as an answer to the problem of re-sale of price-controlled goods, commonly known here as bachaqueo. But they have been facing problems since the start. The most notable is that in most cases the amount of food products they receive is not enough for the communities.

Inés Guzmán, a member of the supply committee of her Communal Council, told me the following story.

We were once asked to attend a meeting to tell us we were going to receive some bags form the CLAP. But we were disappointed. In our area we are 417 families, and in the meeting we were told we would get 200 bags with food. We decided not to accept the offer because we know there are people in our community that are very angry with the food situation. And if we only gave away 200 bags, we could even get beaten up.

It would be an exaggeration to speak of a famine in Caracas’s poorest sectors. But is undeniable that the situation has noticeably changed for the working class. In most cases people are eating only twice a day and are consuming more vegetables because they are less expensive.

Discontent is evident. The many looting attempts in the western Caracas show high levels of frustration and anger in the most populated sectors of the city. However, organized protest, or a generalized social upheaval is not happening for several reasons.

The first reason is an efficient government apparatus that isolates and controls any protest in popular areas. Some months ago there was a looting incident in Carapita, the barrio next to Antímano. If it had extended to other nearby areas, it could have generated a situation similar to the 1989 Caracazo, when people fed up with the economic measures of President Carlos Andrés Pérez, took to the streets to protest and loot.

The people in Carapita had been waiting in line for food since the day before. In the afternoon a truck with food arrived, but it was decided that it would not sell its goods to the public. The crowd exploded in protest and looted the truck. People also tried to loot nearby stores. But in less than five minutes a well-organized battalion of the National Bolivarian Police arrived on the scene firing tear-gas and dispersing the crowd.

A second reason damping the will to protest of the working class is the constant struggle to find food. For most working people life has become an unending hunt for food, and to fail means to go hungry.

Even if most people are aware of the political and economic situation of the country, and reject the administration of President Nicolás Maduro with the same force with which they backed Chávez, there is little space in their lives for active protests. To leave their workplace, or leave the queue to get food to feed their families, is not an option for most people.

This rejection of the Maduro administration, cannot be interpreted as real support for the Venezuelan opposition. In the barrios you will constantly hear calls for a change of government that can improve the economic situation. It is also commonly thought that the only political force capable of achieving change is the opposition under the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática. But the opposition leaders are still perceived as an elite, disconnected from popular feelings.

Political alternatives are a second scarcity suffered by the working class. Venezuela’s polarization has left only two alternatives that do not represent their interests. Thus they align with one side or the other depending on the circumstances.

My neighbor Catalina Ramos says with sadness: “We backed Maduro out of a sense of loyalty with Chávez. But that man has driven us to a bad, bad, bad situation. We have no other option than to change him, put some other person in his place and see if things get better for the country, even if we don’t like that other person.”

Translated by Hugo Perez Hernaiz and David Smilde