Last week the Executive Secretary of the opposition coalition Mesa de la Unidad, Chuo Torrealba caused a kerfuffle within the opposition when he suggested that marriage equality was a “first world” issue and would not be a legislative priority given the current crisis. This generated an immediate response from Venezuela’s transgender opposition deputy Tamara Adrián, whose recent election has generated considerable expectations regarding an advance on this issue. Adrian responded that Torrealba was not a deputy and did not set the legislative agenda. The issue lit up social media over the weekend.

Javier Corrales is a leading Venezuela scholar as well as a leading analyst of the struggle for LGBTQ rights in Latin America, coediting in 2010 The Politics of Sexuality in Latin America: A Reader on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights. Over the weekend he agreed to do an email interview on the issues surrounding the push for marriage equality in Venezuela.

In your research you have looked at marriage equality around the region and the quite different outcomes we have seen between different countries

The remarkable aspect about Latin America is that changes have occurred despite what culture and religion would have dictated. In general, culture (measured in terms of public opinion) and religion (especially degree to which a person attends church rituals) act as huge barriers to the expansion of LGBTQ rights. Except in a few countries, most Latin Americans are opposed to important LGBTQ rights such as same-sex marriage or the right to teach young children, and most highly religious individuals are opposed to LGBTQ rights. A 2014 poll showed that less than 30 percent of Venezuelans approve same-sex marriage. This is very low but also not that atypical.

So all governments and movements that embrace LGBTQ rights engage in a fight against prevailing cultural norms and religious attitudes and leaders. Whether these governments and politicians prevail in changing the law depends of course on many factors. Some of these factors have to do with social movement features (e.g., strategies adopted by social movements). But it also depends on factors that have little to do with social movements per se, for example: type of alliances with other political actors, type of inter-party competition, degrees of federalism, and of course the assertiveness and progressiveness of courts.

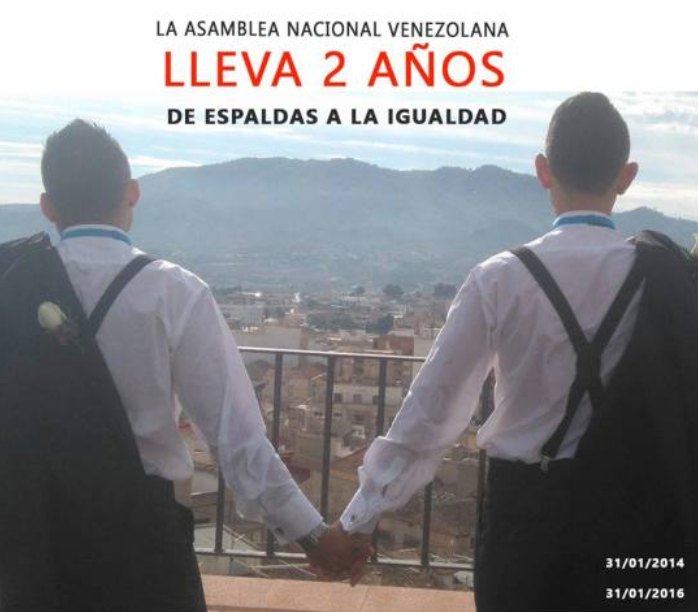

In Venezuela, a coalition of NGOs developed a bill they called the Ley de Amor which they tried to introduce in 2014. However, it was never discussed. Why do you think that happened in a congress dominated by a leftist party that one would think supported the struggles of marginalized groups?

The Venezuelan ruling party has lost interest in extending liberal rights. The ruling party expanded some rights to some communities, but these occurred mostly at the start of Chavismo, and seldom for LGBTQ communities. The ruling party has also not been that interested in allowing for the courts to act independently, and this has foreclosed one way through which LGBTQ rights expand–through court rulings.

There is no question that an important aspect of the Latin American left is very machista, (see chapter by Shawn Schulenberg) far more interested in talking about fighting capitalism than fighting heteronormativity. That is, it is a left that is more Castro-Guevarista than anything else. The Venezuelan ruling party comes from that tradition. In addition, the party has been heavily influenced by evangelicals, none of whom display tolerance for non-heteronormativity.

And finally, and this is crucial, the ruling party has never faced huge pressure from the opposition on this issue either. Up until 2014, social movements advocating same-sex marriage rights were somewhat isolated within Venezuela, in that major actors in the opposition were unwilling to offer them broad support. So as a pressure group, pro-LGBT social movements have been rather weak with little bargaining leverage. To use contemporary language, they have a deficit of organized queer allies. That, however, is changing as we speak.

In the 2015 legislative elections, a trans-gendered candidate, Tamara Adrián won a seat for the opposition as a replacement deputy. This has put the issue back on the agenda. Do you think the sea change in the National Assembly will lead to progress on this issue?

The nomination and then election of Tamara Adrián is a huge event, not just for Venezuela, but also for Latin America and the world, where there are very few openly out LGB politicians, and even fewer trans politicians. I argued already that it was the top LGBTQ event of 2015 for Latin America.

Adrián’s election has already succeeded in expanding the debate in Venezuela on human rights. She was the first to criticize not just the government’s double discourse but also the opposition’s timidity on this issue.

LGBTQ rights are now a national issue, finally. We know from experience that the more the question of LGBT rights gets debated nationwide, in any country, the more likely it is for acceptance to expand, especially among younger voters. Homophobia expands as well, but sometimes less significantly than acceptance. Visibility, exposure, and open discussion is not all that is needed to create a favorable environment for LGBTQ rights, but they are enormously helpful. Adrián has brought visibility, exposure, and open discussion.

Opposition coalition leader Chúo Torrealba recently called marriage equality a “first world” issue and suggested it was not a priority given the crisis in Venezuela. The problem, of course, is that Venezuela will likely be in crisis for years. Do you think there is anything that could break through this logic?

This was an unfortunate but candid revelation about a major aspect of the politics of expanding LGBTQ rights. Very often, politicians make this argument. Sometimes it is sincere: politicians think that they should worry about issues that are more urgent or that affect more than a tiny minority. Other times, the argument serves as a convenient way to hide homophobia, or at least the fact that there is no interest in this issue and would prefer to devote political energy to other topics. In the case of Venezuela, it could be all of the above.

The opposition, like the ruling party, is comprised of groups that are very connected to religious interest groups. So homophobia and heteronormativity are rampant. And the opposition also knows that any political victory in Venezuela will be hard, so they are keen on reserving political capital for other battles.

But the truth of the matter is that all evidence shows that the topic of LGBTQ rights is enormously urgent not just for members of the LGBTQ community, but to an increasingly large number of citizens–from both the left and the right–who feel that it is a litmus test for society. They feel that the prevalence of homophobia is associated with, maybe even symptomatic of, other noxious societal attitudes that hinder human potential, such as intolerance in general, lack of critical and independent thinking, and too much reverence for authority and traditionalism. This explains why LGBTQ rights have become a popular cause among many voters worldwide, not just members of the LGBTQ community. The factors that are sustaining homophobia are the very same factors that preclude social change in other areas.