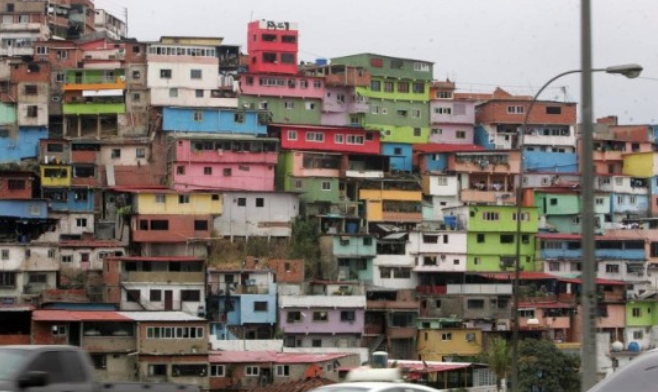

As in previous cycles of protest in the Chávez years, the marches and demonstrations occurring over the past six weeks have mainly been populated by Venezuela’s urban middle classes, although there have been some cases of protests and lootings breaking out in the popular barrios. This has again raised the question of why Venezuela’s poor majorities have not participated en mass and what would happen if they did (see same issue addressed in March 2014 on this blog here and here). This is actually a hypothetical that has been around since before Chávez, and in Venezuela takes the hypothetical form of “si bajen los cerros” (“if the hills come down”—most popular barrios in Caracas are on hillsides.)

One of the most articulate scholars on this question is New York Univeristy historian and Venezuelan national, professor Alejandro Velasco, author of the award-winning book Barrio Rising: Urban Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. In recent weeks he has been interviewed by BBC Mundo (here in Spanish) and O Globo (here in Portuguese) on this question. Below is a translation of one key paragraph from the Globo interview, and the discussion the interview generated on his Facebook timeline among several social scientists who specialize in researching the popular sectors.

To the journalists question of why the barrios do not unify, Velasco responded as follows:

“Because of mistrust, which is deep and extends long before Chávez. The distrust of the poor in relation to the wealthy is the most significant barrier for the population to unify against Maduro. And in parallel, the opposition also distrusts popular sectors, thinking they sold out to Chavismo. But the opposition is fooling itself because popular sectors are not asleep. They are awake and watching. The sensation in western Caracas is that after Maduro something worse could come and that any rebellion might be used for a government that does not favor them. Worse yet, that in the future they could be more even more repressed with the excuse, for example, of combating the so-called collectives (chavista armed groups). There is fear of the middle and long term.”

David Smilde: I totally agree with the logic you put forward, Alejandro. But I wonder whether the percentage of those who are guided by this logic are less now, than in 2014, when it was clearly determinant. I detect a growing sentiment in the popular sectors that this government also does not care about its wellbeing and this changes the equation, not because of what they think of the opposition, which has failed to reach out to them, but what they think of Maduro and other government and party officials. Chavista leaders no longer appear to be the “devils we know.”

There have been protests, street closings, and lootings in the popular sectors that have come as echoes of the opposition protests, which have largely been populated by their traditional base in the urban middle classes. I don’t think this is the beginning of the famous “cuando bajen los cerros” (when the poor come down). But it is a signal that the calculus of some in the popular sectors have changed.

Alejandro Velasco: You basically summarized what I said, but as usual, in a better way.

Dimitris Pantoulas*: I think this idea of “when the barrios come down” is journalistically attractive, but I think that in the current context the questions should be posed in a different way, corresponding better to the country’s political reality. Part of the barrios have already “come down” politically and demonstrated this with their votes in the 2015 elections, as well as with their participation in recent demonstrations, and even more importantly, with their absence in the counter-demonstrations organized by the Maduro government.

Perhaps the question journalists really should ask is why the barrios don’t “burn down Miraflores” and force Maduro to flee, like popular movements did in Bolívia with Sánchez de Lozada in 2003. And in this I agree with Alejandro in his interview that a large part of the barrios distrust the opposition and do not have much clarity on what would happen to them after Maduro.

Those who live in barrios are rational people and they understand that their option is selecting between “different bad dishes” for which they neither select the ingredients nor do the cooking. Some of them, tired and bored by what the Maduro government is offering, prefer a new dish—just as bad, but new. Others are happy with the dish they have, which at least has some content. And others are waiting to see what is going to happen and then will decide where they want to go. This last group is pretty typical of Venezuelan politics in the last fifteen years, including political parties and actors that define their agendas at the last minute. I also think that the majority in the barrios think that the political cost of the political change should be paid by the two principle groups responsible for the problem.

María Pilar García Guadilla*: This is an interesting reflection, Alejandro. I would add that perhaps the poor are more tied to resolving their immediate needs in the short term given that their survival depends on the distribution of bags of food through the Local Committees of Distribution and Production (CLAP), as well as the other prebends, now too scarce to cover all of those who are needy. For this reason, they are more susceptible to manipulation through clientalism: “If you protest, I’ll take away your CLAP bag, I’ll throw you out of your job, I’ll take your public housing away, etc. etc.” The cost of protesting has been and still is very high in the popular sectors.

What I am trying to say is that perhaps it has to do with needs and expectations that are different from those experienced by the middle class and because of this, it is difficult for them to go out and defend elections or political prisoners. When the popular sectors have been “self-mobilized” by hunger or by the terrible violence unleashed by the Operación Liberación del Pueblo, they have expressed themselves as far as possible. And I am sure that they would do so much more vigorously if the repression was not so strong.

I continue to believe, as I have said for some time, that the popular sectors have little or nothing to look for in an opposition that has no agenda, hasn’t had an agenda regarding what to do in the short term to resolve the problem of hunger in the popular sectors. A macroeconomic agenda is not going to help you eat tomorrow! The CLAP distribution program at least helps relieve hunger, even if only once in a while. This could contribute to maintaining some sort of hope in the government, or oblige the popular sectors to maintain some loyalty. In the end, I don’t see any reason why the barrios would come down to demand regional elections or support the other demands made by the opposition.

Mila Ivanovic*: Perhaps the problem here is in trying to take the pulse of 70% of the population. We are victims of a populist reading of the political field and I think it is very difficult to try to analyze THE barrios, in Caracas and the rest of the country. With respect to the CLAPs, I know of experiences in which the communal councils have been revitalized because the CLAP process gives them a permanent agenda for working for the common good. With respect to the lack of liberty in the barrios to protest, that does not seem relevant. Since before the death of Chávez, the barrios have seen an increase in the visibility of opposition parties (particularly Primero Justicia and Voluntad Popular), now with surely a lot more force, since the government’s hegemony has be inverted in numeric terms.

I am not saying that there are not government pressures in some spaces (institutional above all, and also “shock troops”—the so called “collectives”—that are more organized and control part of territorial rents), but the fact that we don’t see more people from the popular sectors (let’s say people with black and brown bodies that are “poorly spoken”—since this what actually distinguishes them from the middle classes in people´s minds) in marches should not be attributed to any kind of “popular authoritarianism.”

Maria Pilar García Guadilla: I think it is essential to do this analysis of the barrios in the current crisis because it is a topic that neither the opposition nor the government is doing. Our study following the CLAPs indicates a high level of politicization and cooptation of the social fabric, as is the case with the communal councils and the communes, with a resulting demobilization around the democratic goals of participatory democracy and inclusion, for which these participatory institutions were created. It is possible that the communal councils in some cases have been revitalized, above all through their role in the distribution of bags of food. But they have been revitalized as clientelistic instances, coopted, politicized, and exclusionary.

Mila Ivanovic: Well politics has always been their objective, which does not mean that they are exclusive in and of themselves. I am not saying that we cannot analyze the barrios but rather that we need to be carefully in making sweeping generalization and try to always carefully situate who and what we are talking about because speaking about the 23 de Enero, Antímano and a barrio in Valencia is very different. With respect to cooptation, given an increasingly disorganized state, I am not sure that this is the most important de-mobilizing factor. The superimposition of partisanship with social-communitarian initiatives is an obvious fact since 1999. But the communal councils continue to be much more heterogeneous than the UBChs (the territorial unit of the PSUV organization) and with internal disputes and open government criticisms. And “clientalism” is a ticket that is applied to the popular sectors when it is part of all political relations.

The fact that there has not been a massive manifestation of the popular classes like there was on April 13, 2002 does not mean that there has not been a reorganization of the opposition in the barrios, nor that there is not other forms of protest that are not part of the main opposition protests. Finally, there is the symbolic factor that remains important: the figure of Chavez used by the government still serves as a limit on the socio political action of the popular sectors, despite the deteriorating living conditions they have been experiencing in recent years.

Alejandro Velasco: Agreed, which is why I wanted to highlight heterogeneity among popular sectors, not just as a way to signal complexity, but as a critical corrective to the question itself. The fact remains that Venezuela’s polarization has gravely accentuated a dynamic at play long before Chavez, and that is a tendency to generalize about what we don’t know, in the process creating caricatures that lend themselves to simplistic scenarios. Just as “the opposition” isn’t a unitary whole, neither is chavismo, and certainly neither are popular sectors whose support for chavismo has always been manifold – sometimes transactional, sometimes ideological, more often because, at long last, someone at the helm of power seemed to speak to and of them in ways that recognized them as agents, not just as dupes. That may be difficult to accept if one is prone already to look at popular politics as unsophisticated or worse. But it’s at the heart of both the distrust that lingers, and of the deeper crisis eating at Venezuela. It has also long been the opposition’s main challenge, it remains so today, and will continue even if it comes to power in the short term.

*Dimitris Pantoulas is a political consultant and Senior Political Associate in the Observatorio Global de Comunicación y Democracia.

*Maria Pilar García Guadilla is Professor of Urban Planning and Political Science at the Universidad Simón Bolívar

*Mila ivanovic is a PhD in political science from the University of Paris and researcher associated to FLACSO-Ecuador